A compass is a navigational instrument that measures directions in a frame of reference that is stationary relative to the surface of the earth. The frame of reference defines the four cardinal directions (or points) – north, south, east, and west. Intermediate directions are also defined. Usually, a diagram called acompass rose, which shows the directions (with their names usually abbreviated to initials), is marked on the compass. When the compass is in use, the rose is aligned with the real directions in the frame of reference, so, for example, the "N" mark on the rose really points to the north. Frequently, in addition to the rose or sometimes instead of it, angle markings in degrees are shown on the compass. North corresponds to zero degrees, and the angles increase clockwise, so east is 90 degrees, south is 180, and west is 270. These numbers allow the compass to show azimuths or bearings, which are commonly stated in this notation.

There are two widely used and radically different types of compass. The magnetic compass contains a magnet that interacts with the earth's magnetic fieldand aligns itself to point to the magnetic poles. The gyro compass (sometimes spelled with a hyphen, or as one word) contains a rapidly spinning wheel whose rotation interacts dynamically with the rotation of the earth so as to make the wheel precess, losing energy to friction until its axis of rotation is parallel with the earth's.

The magnetic compass was invented during the Chinese Han Dynasty between the 2nd century BC and 1st century AD,[1] and was used for navigation by the 11th century.[2] The compass was introduced to medieval Europe 150 years later,[2] where the dry compass was invented around 1300.[3] This was supplanted in the early 20th century by the liquid-filled magnetic compass.[4]

History

The first compasses were made of lodestone, a naturally-magnetized ore of iron. Ancient people found that if a lodestone was suspended so it could turn freely, it would always point in the same direction (toward the magnetic poles). Later compasses were made of iron needles, magnetized by stroking them with a lodestone.

[edit]

See also: Polynesian navigation

Prior to the introduction of the compass, position, destination, and direction at sea were primarily determined by the sighting of landmarks, supplemented with the observation of the position of celestial bodies. On cloudy days, the Vikings may have used cordierite or some other birefringent crystal to determine the sun's direction and elevation from the polarization of daylight; their astronomical knowledge was sufficient to let them use this information to determine their proper heading.[10] For more southerly Europeans unacquainted with this technique, the invention of the compass enabled the determination of heading when the sky was overcast or foggy. This enabled mariners to navigate safely far from land, increasing sea trade, and contributing to the Age of Discovery.

[edit]Geomancy and feng shui

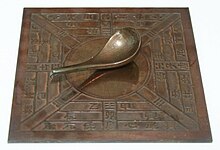

Magnetism was originally used, not for navigation, but for geomancy and fortune-telling by the Chinese. The earliest Chinese magnetic compasses were probably not designed for navigation, but rather to order and harmonize their environments and buildings in accordance with the geomantic principles of feng shui. These early compasses were made using lodestone, a special form of the mineralmagnetite that aligns itself with the Earth’s magnetic field.[11]

Based on Krotser and Coe's discovery of an Olmec hematite artifact in Mesoamerica, radiocarbon dated to 1400-1000 BC, astronomer John Carlson has hypothesized that the Olmec might have used the geomagnetic lodestone earlier than 1000 BC for geomancy, a method of divination, which if proven true, predates the Chinese use of magnetism for feng shui by a millennium.[12] Carlson speculates that the Olmecs used similar artifacts as a directional device for astronomical or geomantic purposes but does not suggest navigational usage. The artifact is part of a polished hematite (lodestone) bar with a groove at one end (possibly for sighting). The artifact now consistently points 35.5 degrees west of north, but may have pointed north-south when whole. Carlson's claims have been disputed by other scientific researchers, who have suggested that the artifact is actually a constituent piece of a decorative ornament and not a purposely built compass.[13][14] Several other hematite or magnetite artifacts have been found at pre-Columbian archaeological sites in Mexico and Guatemala.[15][16]

[edit]

The invention of the navigational compass is credited by scholars to the ancient Chinese, who began using it for navigation sometime between the 9th and 11th century.[14] Europeans and Arabs were first introduced to the compass through nautical contacts during the Chinese Song Dynasty (960–1279).[14] Later the compass appeared in Europe, India, and the Middle East due to the formation of the Mongol Empire which effectly eliminated all previous national barriers within the empire and allowed the safe transfer and transportation of both people and intellectual knowledge across the silk roadfrom China to Europe, the Middle East, and East Africa.

[edit]China

Further information: Four Great Inventions, List of Chinese inventions, and History of science and technology in China

There is disagreement as to exactly when the compass was invented. These are noteworthy Chinese literary references in evidence for its antiquity:

- The earliest Chinese literature reference to magnetism lies in the 4th century BC writings of Wang Xu (鬼谷子): "The lodestone attracts iron."[18] The book also notes that the people of the state of Zheng always knew their position by means of a "south-pointer"; some authors suggest that this refers to early use of the compass.[19]

- The first mention of the attraction of a needle by a magnet is a Chinese work composed between 70 and 80 AD (Lunheng ch. 47): "A lodestone attracts a needle." This passage of Louen-heng is the first Chinese text concerning the attraction of a needle by a magnet.[20] In 1948, the scholar Wang Chen-Tuo constructed a "compass" in the form of south-indicating spoon on the basis of this text. However, "there is no explicit mention of a magnet in the Louen-heng" and that "beforehand it needs to assume some hypotheses to arrive at such a conclusion."[17]

- The earliest reference to a specific magnetic direction finder device is recorded in a Song Dynasty book dated to 1040-44. There is a description of an iron "south-pointing fish" floating in a bowl of water, aligning itself to the south. The device is recommended as a means of orientation "in the obscurity of the night." The Wujing Zongyao (武經總要, "Collection of the Most Important Military Techniques") stated: "When troops encountered gloomy weather or dark nights, and the directions of space could not be distinguished...they made use of the [mechanical] south-pointing carriage, or the south-pointing fish."[21] This was achieved by heating of metal (especially if steel), known today as thermoremanence, and would have been capable of producing a weak state of magnetization.[21] While the Chinese achieved magnetic remanence and induction by this time, a similar discovery was not made in Europe until about 1600, when William Gilbert published his De Magnete.[22]

- The first incontestable reference to a magnetized needle in Chinese literature appears in 1088.[23] The Dream Pool Essays, written by the Song Dynasty polymath scientist Shen Kuo, contained a detailed description of how geomancers magnetized a needle by rubbing its tip with lodestone, and hung the magnetic needle with one single strain of silk with a bit of wax attached to the center of the needle. Shen Kuo pointed out that a needle prepared this way sometimes pointed south, sometimes north.

- The earliest explicit recorded use of a magnetic compass for navigational purposes is found in Zhu Yu's book Pingzhou Table Talks (萍洲可談; Pingzhou Ketan) and dates from 1117:[14] The navigator knows the geography, he watches the stars at night, watches the sun at day; when it is dark and cloudy, he watches the compass.

Thus, the use of a magnetic compass as a direction finder occurred sometime before 1044, but incontestable evidence for the use of the compass as a navigational device did not appear until 1117.

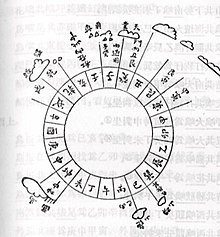

The typical Chinese navigational compass was in the form of a magnetic needle floating in a bowl of water.[24] According to Needham, the Chinese in the Song Dynasty and continuing Yuan Dynastydid make use of a dry compass, although this type never became as widely used in China as the wet compass.[25] Evidence of this is found in the Shilin guangji ("Guide Through the Forest of Affairs"), published in 1325 by Chen Yuanjing, although its compilation had taken place between 1100 and 1250.[25] The dry compass in China was a dry suspension compass, a wooden frame crafted in the shape of a turtle hung upside down by a board, with the lodestone sealed in by wax, and if rotated, the needle at the tail would always point in the northern cardinal direction.[25] Although the European compass-card in box frame and dry pivot needle was adopted in China after its use was taken by Japanese pirates in the 16th century (who had in turn learned of it from Europeans),[26] the Chinese design of the suspended dry compass persisted in use well into the 18th century.[14][27] However, according to Kreutz there is only a single Chinese reference to a dry-mounted needle (built into a pivoted wooden tortoise) which is dated to between 1150 and 1250, and claims that there is no clear indication that Chinese mariners ever used anything but the floating needle in a bowl until the 16th-century.[24]

The first recorded use of a 48 position mariner's compass on sea navigation was noted in a book titled “The Customs of Cambodia” by Yuan Dynasty diplomatZhou Daguan, he described his 1296 voyage from Wenzhou to Angkor Thom in detail; when his ship set sail from Wenzhou, the mariner took a needle direction of “ding wei” position, which is equivalent to 22.5 degree SW. After they arrived at Baria[disambiguation needed  ], the mariner took "Kun Shen needle", or 52.5 degree SW.[28] Zheng He's Navigation Map, also known as "The Mao Kun Map", contains a large amount of detail "needle records" of Zheng He's travel.[29]

], the mariner took "Kun Shen needle", or 52.5 degree SW.[28] Zheng He's Navigation Map, also known as "The Mao Kun Map", contains a large amount of detail "needle records" of Zheng He's travel.[29]

There is a debate over the diffusion of the compass after its first appearance with the Chinese. At present, according to Kreutz, scholarly consensus is that the Chinese invention predates the first European mention by 150 years.[2] However, there are questions over diffusion, because of the apparent failure of the Arabs to function as possible intermediaries between East and West because of the earlier recorded appearance of the compass in Europe (1190)[30] than in the Muslim world (1232, 1242, and 1282).[31][32] The first European mention of a magnetized needle and its use among sailors occurs in Alexander Neckam'sDe naturis rerum (On the Natures of Things), probably written in Paris in 1190.[30] Other evidence for this includes the Arabic word for "Compass" (al-konbas), possibly being a derivation of the old Italian word for compass. In the Arab world, the earliest reference comes in The Book of the Merchants' Treasure, written by one Baylak al-Kibjaki in Cairo about 1282.[31] Since the author describes having witnessed the use of a compass on a ship trip some forty years earlier, some scholars are inclined to antedate its first appearance accordingly. There is also a slightly earlier non-Mediterranean Muslim reference to an iron fish-like compass in a Persian talebook from 1232.[32]

[edit]Medieval Europe

In 1187 Alexander Neckam reported the use of a magnetic compass for the region of the English Channel.[33] In 1269 Petrus Peregrinus of Maricourt described a floating compass for astronomical purposes as well as a dry compass for seafaring, in his well-known Epistola de magnete.[33] In the Mediterranean, the introduction of the compass, at first only known as a magnetized pointer floating in a bowl of water,[34] went hand in hand with improvements in dead reckoning methods, and the development of Portolan charts, leading to more navigation during winter months in the second half of the 13th century.[35] While the practice from ancient times had been to curtail sea travel between October and April, due in part to the lack of dependable clear skies during the Mediterranean winter, the prolongation of the sailing season resulted in a gradual, but sustained increase in shipping movement; by around 1290 the sailing season could start in late January or February, and end in December.[36] The additional few months were of considerable economic importance. For instance, it enabled Venetian convoys to make two round trips a year to the Levant, instead of one.[37]

At the same time, traffic between the Mediterranean and northern Europe also increased, with first evidence of direct commercial voyages from the Mediterranean into the English Channel coming in the closing decades of the 13th century, and one factor may be that the compass made traversal of theBay of Biscay safer and easier.[38] However, critics like Kreutz feel that it was later in 1410 that anyone really started steering by compass.[39]

At present, according to Kreutz, "barring the discovery of new evidence, it seems clear the first Chinese reference to" the compass "antedates any European mention by roughly 150 years."[2] However, there are questions over diffusion, because of the apparent failure of the Arabs to function as possible intermediaries between East and West because of the earlier recorded appearance of the compass in Europe (1190)[30] than in the Muslim world (1232, 1242, and 1282).[31][32] This is countered by evidence of the temporal proximity of the Chinese navigational compass (1117) to its first appearance in Europe (1190) and the common shape of the early compass as a magnetized needle floating in a bowl of water.[30]

[edit]Islamic world

The earliest reference to an iron fish-like compass in the Islamic world occurs in a Persian talebook from 1232.[32] This fish shape was from a typical early Chinese design.[14] The earliest Arabic reference to a compass - in the form of magnetic needle in a bowl of water - comes from the Yemeni sultan andastronomer Al-Ashraf in 1282.[31] He also appears to be the first to make use of the compass for astronomical purposes.[40] Since the author describes having witnessed the use of a compass on a ship trip some forty years earlier, some scholars are inclined to antedate its first appearance in the Arab worldaccordingly.[32]

In 1300, another Arabic treatise written by the Egyptian astronomer and muezzin Ibn Simʿūn describes a dry compass for use as a "Qibla (Kabba) indicator" to find the direction to Mecca. Like Peregrinus' compass, however, Ibn Simʿūn's compass did not feature a compass card.[33] In the 14th century, the Syrianastronomer and timekeeper Ibn al-Shatir (1304–1375) invented a timekeeping device incorporating both a universal sundial and a magnetic compass. He invented it for the purpose of finding the times of Salah prayers.[41] Arab navigators also introduced the 32-point compass rose during this time.[42]

[edit]India

The compass was used in India for navigational purposes and was known as the matsya yantra, because of the placement of a metallic fish in a cup of oil.[43]

[edit]Medieval Africa

There is evidence that the distribution of the compass from China likely also reached eastern Africa by way of trade through the end of the Silk Road that ended in East African center of trade inSomalia and the Swahili city-state kingdoms. There is evidence that Swahili maritime merchants and sailors acquired the compass at some point and used them for navigation of Swahili versions ofdhows.[44][not in citation given]

[edit]Later developments

[edit]Dry compass

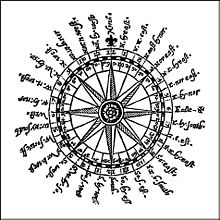

The dry mariner's compass was invented in Europe around 1300. The dry mariner's compass consists of three elements: A freely pivoting needle on a pin enclosed in a little box with a glass cover and a wind rose, whereby "the wind rose or compass card is attached to a magnetized needle in such a manner that when placed on a pivot in a box fastened in line with the keel of the ship the card would turn as the ship changed direction, indicating always what course the ship was on".[3] Later, compasses were often fitted into a gimbal mounting to reduce grounding of the needle or card when used on the pitching and rolling deck of a ship.

While pivoting needles in glass boxes had already been described by the French scholar Peter Peregrinus in 1269,[45] and by the Egyptian scholar Ibn Simʿūn in 1300,[33] traditionally Flavio Gioja (fl. 1302), an Italian pilot from Amalfi, has been credited with perfecting the sailor's compass by suspending its needle over a compass card, thus giving the compass its familiar appearance.[46] Such a compass with the needle attached to a rotating card is also described in a commentary on Dante's Divine Comedy from 1380, while an earlier source refers to a portable compass in a box (1318),[47] supporting the notion that the dry compass was known in Europe by then.[24]

[edit]Bearing compass

A bearing compass is a magnetic compass mounted in such a way that it allows the taking of bearings of objects by aligning them with the lubber line of the bearing compass.[48] A surveyor's compass is a specialized compass made to accurately measure heading of landmarks and measure horizontal angles to help with map making. These were already in common use by the early 18th century and are described in the 1728 Cyclopaedia. The bearing compass was steadily reduced in size and weight to increase portability, resulting in a model that could be carried and operated in one hand. In 1885, a patent was granted for a hand compass fitted with a viewing prism and lens that enabled the user to accurately sight the heading of geographical landmarks, thus creating the prismatic compass.[49] Another sighting method was by means of a reflective mirror. First patented in 1902, the Bézard compass consisted of a field compass with a mirror mounted above it.[50][51] This arrangement enabled the user to align the compass with an objective while simultaneously viewing its bearing in the mirror.[50][52]

In 1928, Gunnar Tillander, a Swedish unemployed instrument maker and avid participant in the sport of orienteering, invented a new style of bearing compass. Dissatisfied with existing field compasses, which required a separate protractor in order to take bearings from a map, Tillander decided to incorporate both instruments into a single instrument. His design featured a metal compass capsule containing a magnetic needle with orienting marks in its base, fitted into a baseplate marked with a lubber line (later called a direction of travel indicator). By rotating the capsule to align the needle with the orienting marks, the course bearing could be read at the lubber line. Moreover, by aligning the baseplate with a course drawn on a map - ignoring the needle - the compass could also function as a protractor. Tillander took his design to fellow orienteers Björn and Alvar Kjellström, who were selling basic compasses, and the three modified Tillander's design. In December 1932, the Silva Company was formed, and the three men began manufacturing and selling their Silva compass to Swedish orienteers, outdoorsmen, and army officers.[53][54][55]

[edit]Liquid compass

The liquid compass is a design in which the magnetized needle or card is damped by fluid to protect against excessive swing or wobble, improving readability while reducing wear. A rudimentary working model of a liquid compass was introduced by Sir Edmund Halley at a meeting of the Royal Society in 1690.[56]However, as early liquid compasses were fairly cumbersome and heavy, and subject to damage, their main advantage was aboard ship. Protected in abinnacle and normally gimbal-mounted, the liquid inside the compass housing effectively damped shock and vibration, while eliminating excessive swing and grounding of the card caused by the pitch and roll of the vessel. The first liquid mariner's compass believed practicable for limited use was patented by the Englishman Francis Crow in 1813.[57][58] Liquid-damped marine compasses for ships and small boats were occasionally used by the British Royal Navy from the 1830s through 1860, but the standard Admiralty compass remained a dry-mount type.[59] In the latter year, the American physicist and inventor Edward Samuel Ritchie patented a greatly improved liquid marine compass that was adopted in revised form for general use by the U.S. Navy, and later purchased by the Royal Navy as well.[60]

Despite these advances, the liquid compass was not introduced generally into the Royal Navy until 1908. An early version developed by RN Captain Creak proved to be operational under heavy gunfire and seas, but was felt to lack navigational precision compared with the design by Lord Kelvin:

Captain Creak's first step in the development of the liquid compass was to introduce a "card mounted on a float, with two thin and relatively short needles, fitted with their poles at the scientifically correct angular distances, and with the centre of gravity, centre of buoyancy, and the point of suspension in correct relation to each other...The compass thus designed rectified the defects of the Admiralty Standard Compass...with the additional advantage of considerable steadiness under heavy gunfire and in a seaway... The one defect in the compass as developed by Creak up to 1892 was that "for manoeuvring purposes it was inferior to Lord Kelvin's compass, owing to comparative sluggishness on a large alteration of course through the drag on the card by the liquid in which it floated...[4][61]

However, with ship and gun sizes continuously increasing, the advantages of the liquid compass over the Kelvin compass became unavoidably apparent to the Admiralty, and after widespread adoption by other navies, the liquid compass was generally adopted by the Royal Navy as well.[4]

Liquid compasses were next adapted for aircraft. In 1909, Captain F.O. Creagh-Osborne, Superintendent of Compasses at the British Admiralty, introduced his Creagh-Osborne aircraft compass, which used a mixture of alcohol and distilled water to damp the compass card.[62][63] After the success of this invention, Capt. Creagh-Osborne adapted his design to a much smaller pocket model[64] for individual use[65] by officers of artillery or infantry, receiving a patent in 1915.[66]

In 1933 Tuomas Vohlonen, a surveyor by profession, applied for a patent for a unique method of filling and sealing a lightweight celluloid compass housing or capsule with a petroleum distillate to dampen the needle and protect it from shock and wear caused by excessive motion.[67] Introduced in a wrist-mount model in 1936 as the Suunto Oy Model M-311, the new capsule design led directly to the lightweight liquid field compasses of today.[67]

]

Building orientation

Evidence for the orientation of buildings by the means of a magnetic compass can be found in 12th century Denmark: one fourth of its 570 Romanesque churches are rotated by 5-15 degrees clockwise from true east-west, thus corresponding to the predominant magnetic declination of the time of their construction.[68] Most of these churches were built in the 12th century, indicating a fairly common usage of magnetic compasses in Europe by then.[69]

Mining

The use of a compass as a direction finder underground was pioneered by the Tuscan mining town Massa where floating magnetic needles were employed for determining tunneling and defining the claims of the various mining companies as early as the 13th century.[70] In the second half of the 15th century, the compass became standard equipment for Tyrolian miners. Shortly afterwards the first detailed treatise dealing with the underground use of compasses was published by a German miner Rülein von Calw (1463–1525).[71]

]Astronomy

Three astronomical compasses meant for establishing the meridian were described by Peter Peregrinus in 1269 (referring to experiments made before 1248)[72] In the 1300s, an Arabic treatise written by the Egyptian astronomer and muezzin Ibn Simʿūn describes a dry compass for use as a "Qibla indicator" to find the direction to Mecca. Ibn Simʿūn's compass, however, did not feature a compass card nor the familiar glass box.[33] In the 14th century, the Syrian astronomer and timekeeper Ibn al-Shatir (1304–1375) invented a timekeeping device incorporating both a universal sundial and a magnetic compass. He invented it for the purpose of finding the times of Salah prayers.[41] Arab navigators also introduced the 32-point compass rose during this time.[42]

No comments:

Post a Comment